Recently, the genomes of nearly 800 prehistoric human individuals have been successfully analyzed as part of a large-scale archaeogenetic program carried out in an extensive European and American collaboration. The results of the research were published in Nature on the 22nd December 2021.

The aim of the project was to map the population movements reaching the British Isles in the second half of the Bronze Age (1300–800 BC). This wave of immigration may have been related to the spread of Celtic languages and may have formed the basis of later Iron Age populations on the British Isles.

In order to gain a better understanding of the Bronze Age and Iron Age population processes in Europe, DNA samples were examined from many regions of the continent, including also the territory of present-day Hungary. The Central European archaeological finds proved to be essential reference materials in these studies. All this data will serve as a basis for answering the Iron Age population history questions of the region in future research.

During the project, the research carried out in Hungary was coordinated by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy (Institute of Archaeogenomics, Research Centre for the Humanities, Eötvös Loránd Research Network) and Tamás Hajdu (Department of Biological Anthropology, Eötvös Loránd University and Department of Anthropology of the Hungarian Natural History Museum).

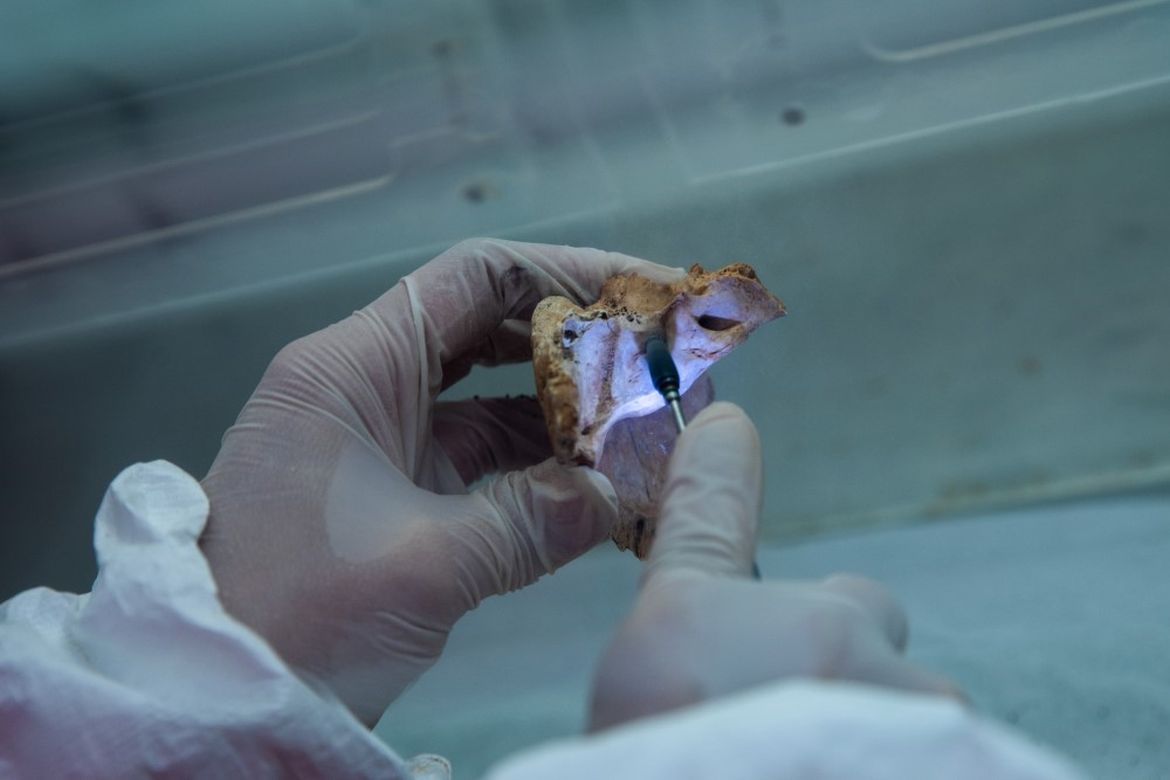

Laboratory cleaning of human petrous bone before DNA sampling at the Institute of Archaeogenomics of the Research Center for the Humanities, Eötvös Loránd Research Network.

Laboratory cleaning of human petrous bone before DNA sampling at the Institute of Archaeogenomics of the Research Center for the Humanities, Eötvös Loránd Research Network.

(Photo: Márton Ficsor)

The research team, led by researchers at York University, Harvard Medical School and the University of Vienna, found that in the second half of the Bronze Age (1300-800 BC), the gene pool of early farmers living in Europe since the Neolithic period resurged and became dominant. As a result, the genes of the Late Bronze Age populations of Central and Western Europe became more similar.

Aerial photo of Gór-Kápolnadomb (Civertan Graphic Studio / Balázs Jászai), which was inhabited or used in prehistoric and medieval times.

Aerial photo of Gór-Kápolnadomb (Civertan Graphic Studio / Balázs Jászai), which was inhabited or used in prehistoric and medieval times.

Bridle (horse harness) from red deer antler found in a pit also containing human bones in the settlement from the Late Bronze Age. (Photo: Gábor Ilon)

Nearly half of the population of South England was replaced during the studied Bronze Age period. However, this process may not have been the result of a one-off and drastic migration, but probably the result of smaller-scale relocations and marriages that accompanied trade relations with the communities in the territory of present-day France.

Excavation photo of a late Bronze Age multiple burial site at Cliffs End Farm in Kent. Human samples have also undergone DNA and various isotope analyzes, which confirmed the distant origins of those buried in the 10-9th century BC.

Excavation photo of a late Bronze Age multiple burial site at Cliffs End Farm in Kent. Human samples have also undergone DNA and various isotope analyzes, which confirmed the distant origins of those buried in the 10-9th century BC.

In addition to utensils, a cattle head and two newborn lambs were placed in the pit during the funeral. (Photo: Wessex Archeology)

By this time of the Bronze Age, extensive trade routes had already networked the significant part of Europe, transporting over long distances bronze tools and the raw materials needed to produce them. New findings suggest that these trade links may in some cases have led to remarkable population mixing, with a significant impact on the composition of Europe's later populations.

Unlike the Bronze Age, genetic analysis found no evidence of major population movement in the genetic ancestry of Iron Age communities. From this results we can conclude that Celtic-speaking groups arrived in the British Isles earlier, during the Bronze Age.

|

An extensive collection and research network in Hungary participated in the research. The archaeological and anthropological background research and the collection materials were provided by the following Hungarian researchers and institutions: Katalin Almássy (earlier Jósa András Museum, Nyíregyháza) Hungarian archaeogenetic partners of the international research group: Anna Szécsényi-Nagy and Balázs Gusztáv Mende (Institute of Archaeogenomics, Research Centre for the Humanities, Eötvös Loránd Research Network, Budapest) Further informations: Hajdu Tamás and Anna Szécsényi-Nagy Link to the article: |