A new paper with a focus on archaeogenomics on the history of horse domestication has been published in Nature, in which the authors also report on the results of their study of Bronze Age artefacts from Hungary. Within the framework of the Pegasus project funded by the European Research Council (ERC), a 162-member research team led by Ludovic Orlando at the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics in Toulouse (CAGT), archaeologists, archaeozoologists and archaeogeneticists from the Rippl-Rónai Museum in Kaposvár and the Institute of Archaeogenomics and the Institute of Archaeology of the ELKH Research Centre for the Humanities (RCH all participated in a large-scale study. By genomically analyzing the remains of 273 ancient horses, the researchers have provided new insights into the origin and distribution of the modern-day domestic horse in a broad international collaboration.

The domestication of the horse brought about a major technological change in the history of mankind, and its versatile use led to a major social transformation. Although equids originated on the North American continent, true wild horses are now only found on the Mongolian steppes and in wildlife reserves and zoos. This subspecies and lineage is called Przewalski’s horse, commonly known as the Mongolian wild horse, after its former descriptor, and it is in the Hortobágy National Park that the world’s largest semi-wild population – 300 individuals – is found. Incidentally, only domesticated or closely related forms of the species are still extant today. This was not the case in prehistoric times, as the results of this study have identified a total of six lineages, with genetic data suggesting that many more may have existed.

Mongolian wild horse (Source: Claudia Feh/Wikipedia)

Mongolian wild horse (Source: Claudia Feh/Wikipedia)

The oldest of the six lineages, Equus lenensis, already known to palaeontologists, was found in the eastern region of Siberia, in what is now Yakutia, where individuals lived from the Pleistocene era until the 4th millennium BC. The individuals described in the study are around 45-50,000 years old, and their genetic heritage, like that of the second oldest lineage, a population also found in Siberia around the Ural Mountains, now shows only small traces, with both groups now essentially extinct. Two of the other major lineage groups that are important for domestication were closely related. These are the Iberian horses that were once widespread in Western Europe, and the horses described from Neolithic times that were widespread in East-Central Europe.

The fifth group includes the modern Przewalski’s horses and their ancestors, which spread across the Eurasian steppes. This was the Botai group, which an earlier study by the working group had shown to be the horses domesticated the earliest, in around 3500 BC. These results have shown that the modern Mongolian wild horse, although presumably retaining the characteristics of the true wild horse, can no longer be considered a wild horse in the literal sense of the word, but merely a feral, tamed horse. The supposed ancestor of the Botai group, the Anatolian subgroup, lived around 6000 BC in what is now Turkey. Genetic traces of this can also be found in certain Central European regions, including – to a small extent – in Hungarian wild horses. This component is completely absent from the Caucasian and Eastern European areas, so it is likely that the Anatolian group may have been linked to the steppe Botai group via the southern Caspian Sea region.

The sixth group, known as DOM2, which is clearly the direct ancestor of modern domestic horses, has been observed since the 6th millennium BC in the western steppe, between the Don and Volga rivers. The coexisting groups – European, Botai and DOM2 – have geographically contiguous distribution ranges, known as contact zones, which are interestingly well demarcated genetically, so that the impact of human intervention in later times can be easily detected in horses.

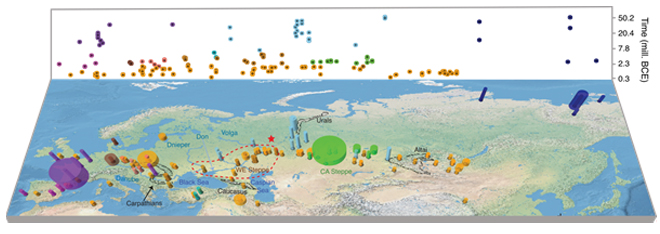

Geographical and chronological relationships of the samples and groups included in the study. The width of the cylinder indicates the sample number, and its height shows the time period.

Geographical and chronological relationships of the samples and groups included in the study. The width of the cylinder indicates the sample number, and its height shows the time period.

Based on color: purple: Iberian group, reddish-orange: Central and Eastern European group, yellowish-orange: DOM2, green: Botaian group, turquoise: Anatolian subgroup, light blue: Uralic group, dark blue: Equus lenensis.(Source: Librado et al., 2021)

The mass occurrence of horses belonging to DOM2 can be associated with the Maykop, Poltavka and Yamnaya archaeological cultures (3500-2600 BC). In the context of these archaeological cultures, there appears to be a connection with Indo-European and Indo-Roman languages and their subsequent spread in Europe and Asia. Furthermore, the evolution of the human genome in Europe and, especially, in Central and West Asia, can be linked to this period. It has long been assumed that horses and horse-drawn carts as tools of warfare and migration made a significant contribution to the spread of these communities, but recent archaeological findings and the current study refute these ideas. The practice of keeping horses appeared and spread in Europe at around the same time as the genetic and archaeological traces of the above-mentioned cultures, and became a common practice from modern Spain to Russia. This expansion was not followed by the emergence of the DOM2 group. Instead, for more than a thousand years, until around 2200 BC, only the remains of horses with a genetic composition specific to the region can be found in the vicinity of prehistoric settlements, i.e. communities from the steppe or with a steppe connection only took over the practice of horse-rearing, but not the horses themselves, in the new areas.

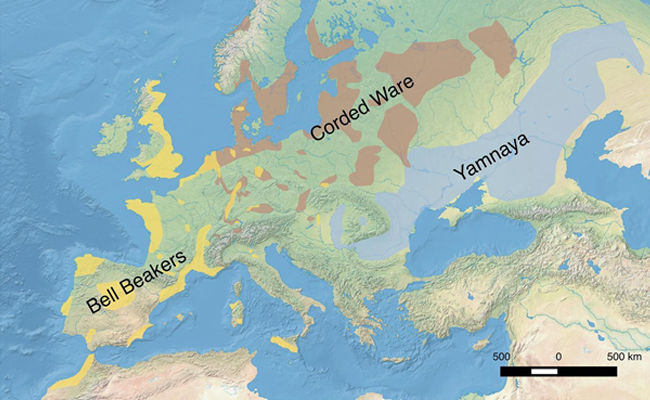

Unfortunately, it was not possible to extract sufficient amounts of cellular DNA from the majority of the horse remains from Hungary that were examined during the research. The reason for this is likely to be that the majority of the remains are scattered bones or bone fragments recovered from storage or rubbish pits excavated in prehistoric settlements, which may have been caused significant damage to the DNA in prehistoric times. At the same time, a sufficient amount of DNA was recovered from two remains for research. One of them is a previously examined sample from Dunaújváros, dated between 2140-1980 BC, and associated with the late Nagyrév and Vatya cultures. The other is a newly investigated sample from Kaposújlak (Somogy County), dating from 2560-2410 BC, which is associated with the Somogyvár-Vinkovci culture. Both have proven to be exceptionally valuable for the understanding of horse rearing in the Carpathian Basin, as they show characteristics of the ancient East-Central European genetic stock. Although the Kaposújlak specimen contained small amounts of eastern genetic components from the Anatolian and DOM2 groups, this was probably due to the natural contact zone independent of humans. The research revealed that, with the exception of these rare but naturally occurring contact zones, the DOM2 component was not present in the Corded Ware culture, which has a significant human genetic heritage of the steppe, and the horse population associated with this and many other European populations consisted essentially of locally captured wild horses and their descendants. More detailed research into local conditions will be carried out as technology develops and more finds become available.

The area of distribution of Bell Beaker, Corded Ware and Pit Grave (Yamnaya) cultures (Source: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

The area of distribution of Bell Beaker, Corded Ware and Pit Grave (Yamnaya) cultures (Source: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

The widespread expansion of the DOM2 group began around 2200 BC. By around 1000 BC, it had displaced the local, indigenous horse breeds not only in Europe but also in Asia. The exception to this is the Tarpan, which became extinct at the beginning of the 20th century and was the last remnant of the rich European diversity that once existed, since it had one-third of the genetic heritage of the European group, presumably the horses of the Corded Ware culture.

The only known photograph of a Tarpan horse from the Moscow Zoo (Source: Wikipedia)

The only known photograph of a Tarpan horse from the Moscow Zoo (Source: Wikipedia)

The emergence of horse rearing for warfare in the Eastern European steppe can be traced back to the Sintashta culture (2200-1800 BC). The results of the new study also confirm that horse-keeping has indeed made a significant contribution to the spread of this cultural unit in Asia, but further research is needed to understand the European processes in more detail. It was also during this period that stables and selective breeding began to appear, giving the DOM2 group a number of genetic traits, mainly physical and temperamental, that made them suitable for the spread of modern civilizations. This study, which explores the complex process full of dead ends that led to the domestication of horses, will serve as a basis for many future studies, helping to unravel hitherto unknown chapters in human history.